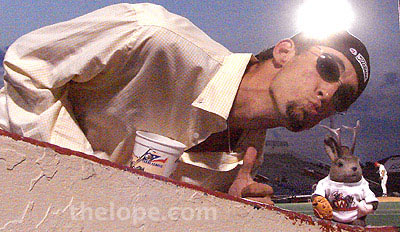

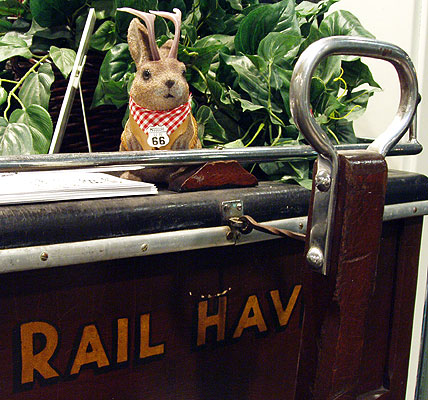

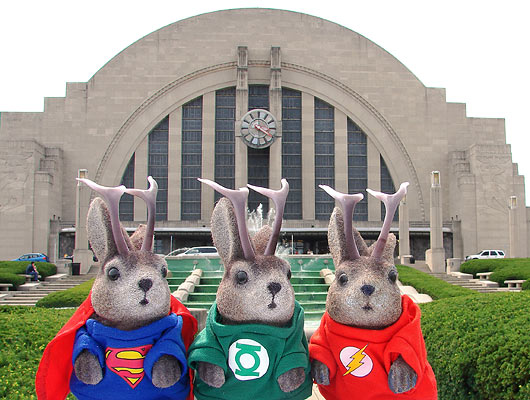

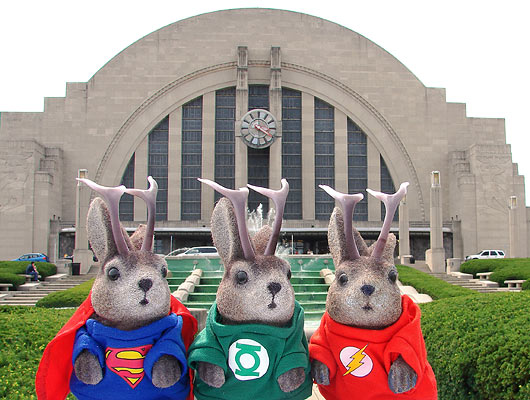

Ace Jackalope inspects the grounds of the Cincinnati Union Terminal.

The

Cincinnati Union Terminal combines at least three very cool things: art deco, natural science and trains. And there's even a pop culture connection for icing on the cake: What do Ace Jackalope, Batman, Stan Marsh, Peter Griffin and Harvey Birdman have in common? Read on and see.

The 1933 art deco masterpiece was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1977. It is ten stories tall, faced with limestone and is approached from the east through a quarter-mile long plaza with landscaping and a fountain.

On either side of the main doors, bas-relief figures designed by Maxfield Keck symbolize Commerce and Transportation.

I really couldn't tell you which one is supposed to be which.

This building bears the date, 1931. Construction began in 1929 and was completed in 1933. For those of you who study architects, Roland A. Wank of Fellheimer and Wagner served as the principal architect, with help from Paul Philippe Cret. The stations website gives

Union Terminal Architectural Information and some

history.

We entered the structure just before noon on July 2, 2006. We were with a party of four adults and two kids; we'd all decided this would be a place where everybody could find their fun, and we were right.

You know it's a good sign when door hardware hasn't been replaced; these art deco door pulls were a good omen.

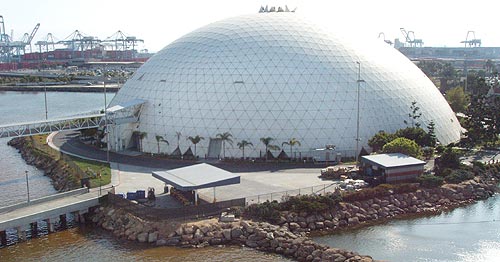

The main doors open into a cavernous open half-dome rotunda. The acoustic ceiling plaster is striking with its arched bands in shades of yellow and orange. The marble in the building is Red Verona. The Rotunda interior dome is 180 feet wide and 106 feet tall.

The digital clock on the present-day information kiosk was on the original Rotunda magazine stand.

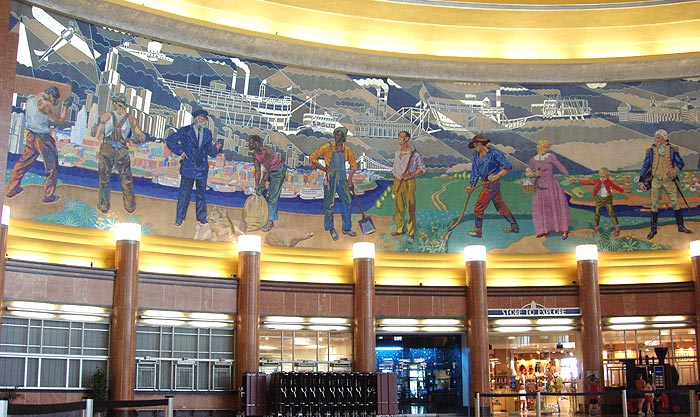

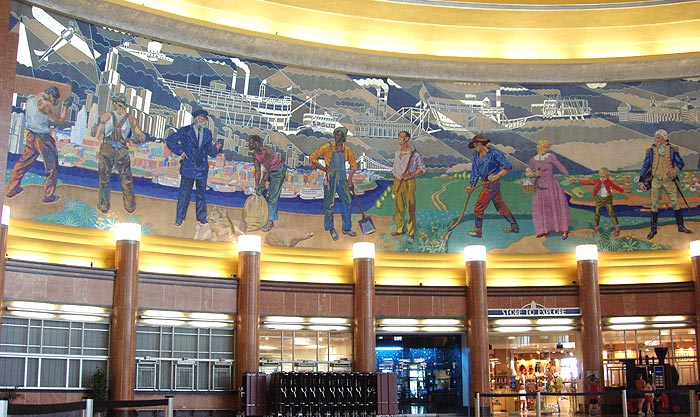

German-born artist Winold Reiss designed

mosaic murals for the station in 1932, two of which still look down on the rotunda.

The 12-foot foreground figures show the roles of people in the developing Cincinnati area. The middle ground shows the evolution of transportation. The abstract background shows landscapes - from the fields settlers found to the city they built. Each mural is 105-feet long and over 20-feet high. This one, to the left of the main entrance as you go in, depicts the settlement of the area from Native Americans through steel workers and transportation from dogs and horses through trains. I find artwork like this is really put in its time context to me by the realization that the steam engine shown is state of the art ground transportation for the time.

The mosaic to the right of the entrance depicts the growth of Cincinnati - transportation from flatboat to airplane and local people from the soldiers at nearby Fort Washington to industrial workers. Reiss used many Cincinnatians as models for this artwork.

There is a mosaic near the entry to an Omnimax theater, but it was more of a tribute to specific businessmen so I didn't shoot it; no disrespect intended, but it exceeded my glorification of the industrial/political figure threshold. There

were 14 other mosaics by Reiss which saluted specific Cincinnati businesses, but those were moved to the Northern Kentucky/Greater Cincinnati International Airport back in the 1970s before a long concourse to the rear of the terminal was destroyed. They can still be seen at the airport in terminals one, two and three. One mosaic was destroyed in 1974 in a previous renovation of part of the structure by the Southern Railway, an act the railway has reportedly said they regret.

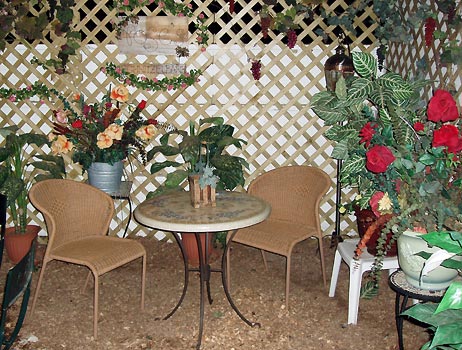

Off to the left of the central rotunda is the Cincinnati Dining Room, used for meetings and social functions. It was closed that day with a "no admittance" sign; I poked my camera in, anyway.

I didn't have time to check into this; I wonder if it's the remainder of an original diner in the station.

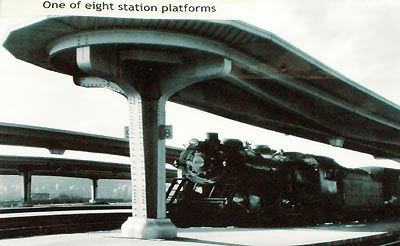

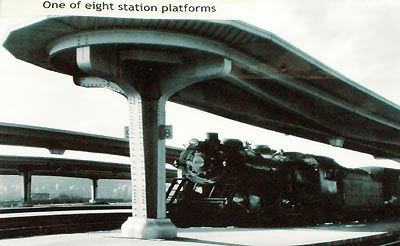

For many years, Cincinnati Union Terminal was a thriving place. When it opened in 1933, the terminal was served by seven railroads: the Baltimore & Ohio, the Chesapeake & Ohio, the Louisville & Nashville, the Norfolk & Western, the New York Central, the Pennsylvania and the Southern. The station could, and did, accommodate 17,000 passengers and 216 trains - 108 in and 108 out - daily. During World War II, the terminal served as a major transfer point for soldiers and saw as many as 34,000 passengers on some days. The train platforms pictured in the museum photo above are gone now, but many a tearful parting or reunion took place beneath them.

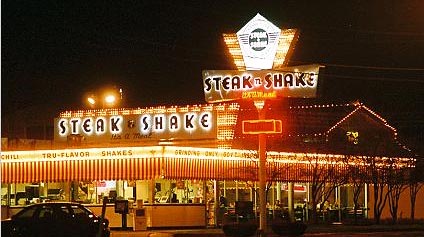

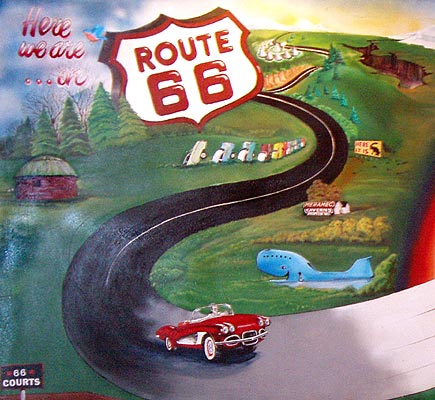

Times change. In the 1950s, the expansion of interstates, the "car culture" and the increasing affordability of airline travel led to the rapid decline of the railroad industry. By the early 1970s, only two trains a day passed through Union Terminal; the last passenger train left the Terminal Saturday evening, October 28, 1972. The huge station languished like a cathedral who's once zealous followers abandoned the religion of the rails for that of the highway. Ironically, this fed one of my other passions - the pursuit of mid 20th century roadside architecture. I guess, either way, I win.

Since its closure, the terminal survived partial destruction and an unsuccessful attempt to turn it into a shopping mall. In the late 1980s, the building was renovated and reopened as Cincinnati Museum Center in 1990. A natural history museum and a Cincinnati history museum now occupy the wings of the building that once served as passageways for cars, taxis and busses to pick up and drop off rail passengers.

History affords some nice twists: passenger service resumed when Amtrak began operating at Union Terminal on July 29, 1991, largely due to the success of the museums in the rejuvenated station.

The

Museum of Natural History & Science, now occupies the right wing of the building, as you go in. This view shows art deco, a reference to trains, and a huge fossil animal; it could scarcely get better, as far as my tastes are concerned.

This totem pole was carved in a Cincinnati department store in 1959 by Amos Wallace, a Tlingit Indian, to celebrate Alaska's entry as the 49th state. Each part of the carving represents something. For example, the top figure is the mythical bird who created the universe and below that is the north star.

There was a also a nice display of Native American beadwork.

This one is Chippewa from 1885.

This one is labeled "Northern Plains circa 1915".

This is the entrance to

Cincinnati's Ice Age: Clues Frozen in Time, an exhibit which details the end of the last ice age in the Ohio Valley, 19,000 years ago.

Giant Beavers once roamed the Ohio valley.

While it is known that dire wolves once roamed the area, the presence of jackalopes in prehistoric Ohio is entirely this website's own conjecture.

Some of my favorite prehistoric dioramas involve the plethora of life forms that pre-date dinosaurs and other more familiar animals. I featured an Ordovician diorama from the museum in another post about a

fossil I saw in a flowerbed in Ohio.

This amphibian is losing its watery environment in the Permian period, 225 million years ago, as sea levels dropped and coastal swamps dried up. As if that wasn't challenge enough, most species were destroyed in a mass extinction at the end of the Permian, the largest mass extinction known. (The plaque for this diorama listed a lungfish and I mistakenly paraphrased that - mistake corrected.)

There are few amimals I love more than the giant armored fish of the Devonian period ("age of fishes"), 400-360 million years ago. This is the head of a Dunkleosteus terrelli, a 25+ foot terror which swam the ocean that once covered Ohio and the surrounding states. Those are not true teeth; they are bony plates that sheared past each other like scissors.

Bothriolepis maxima was a smaller, bottom-dwelling armored fish of the Devonian. It probably walked along the bottom of the sea, and looked very neat doing so.

This model of Stegosaurus, a Jurassic dinosaur was sculpted by Charles Knight, my favorite paleo-artist. It's quite out of date, but I love it all the more as a time capsule of paleontological thought in the very early 20th century.

As I recall, life-sized recreations of dinosaurs began to populate smaller museums in the 1980s; I wish more had been around when I was a kid. This is a model of Allosaurus, a Jurassic predator.

A centerpiece of the museum is a walk-though recreation of a cave entitled

The Cavern: A World Without Light. Different color temperatures of lights made for fun viewing in the "cave."

Remember, stalactites cling "tight"; to the ceiling.

Ace checks out a simulated underground stream, I found the cave to be more amusing than educational, but it was different, at least.

The

Cincinnati History Museum, opened in 1990, is entered through the old "Outgoing Taxis and Motorcoaches" doorway to your right as you enter the terminal.

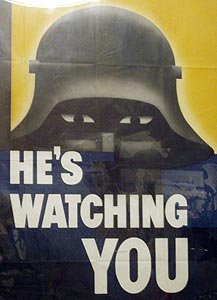

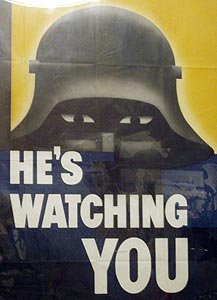

Exhibits include

Cincinnati Goes to War: A Community Responds to WWII.

Cincinnati in Motion

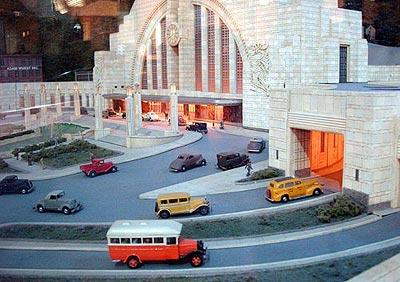

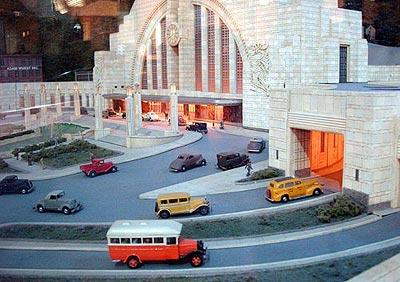

Cincinnati in Motion is a huge S-scale (1/64) urban layout of Cincinatti from 1900 through 1940, complete with working trains, streetcars, inclines and interactive computer stations.

It includes this model of Cincinatti Union terminal, which shows the curved "wings" better than do my exterior photos.

Other exhibits spotlight industry in Cincinnati. Of course, I'm a sucker for an old neon sign.

The artist of this 1910 poster for the Ohio Valley Exposition is not noted on the accompanying label, but it seems imitative of the art nouveau works of

Alphonse Mucha.

Union Terminal also hosts the

Cinergy Children's Museum and an Omnimax theater. But the chief attraction to me was yet to come, up a few flights of non-descript stairs away from the crowds.

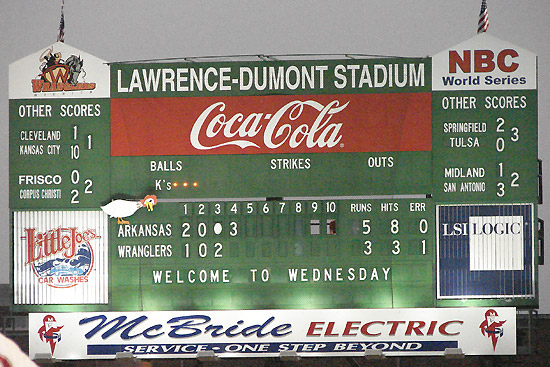

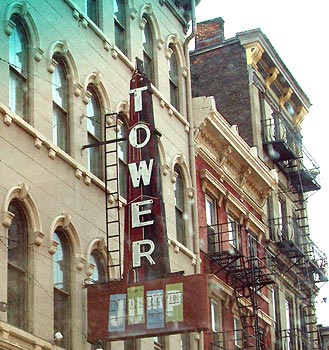

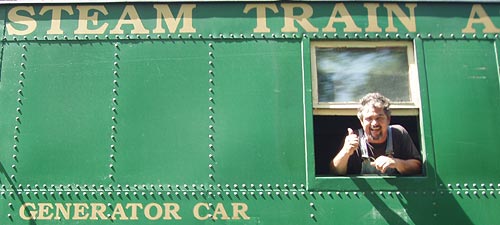

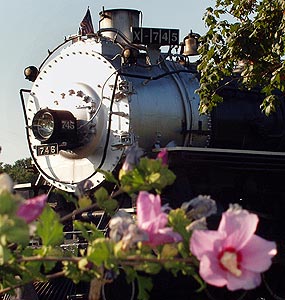

Atop the Cincinnati Union Terminal sits a railfan's playhouse,

Tower A, home of the

Cincinnati Railroad Club.

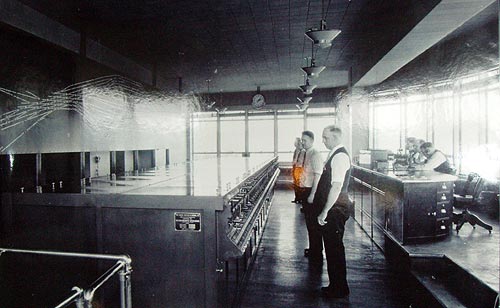

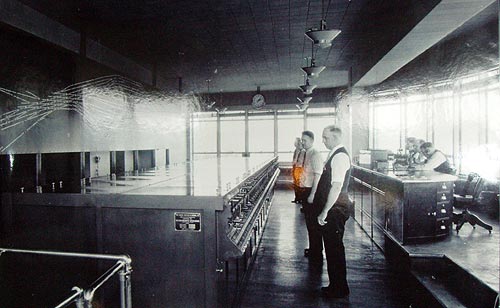

The tower is a long room in back of the dome structure, high above the large railroad yard behind the station. You can see it in this old photograph stored near the tower. Tower A is the high, block-like room in the exact center of the photo. I should note that the long concourse structure coming out from the station has been destroyed, as noted earlier in this post.

Tower A is visible in the distance behind the steam locomotive in this photo on display in the tower.

This is the view looking South from the tower. In the distance, a train crosses a bridge over the Ohio River into Kentucky.

Ace checks out the view to the North, over this truly massive railroad yard. This is the same location from which

Where is Ace Jackalope? (episode 1) was shot.

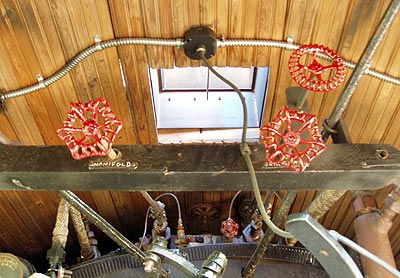

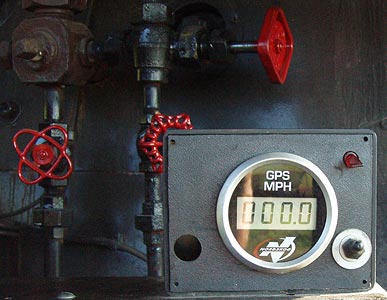

Back in 1933, when Cincinnati Union Terminal was new and had zillions of trains everyday, Tower A was analogous to a modern air traffic control tower. Switches in the railroad yard were controlled by men throwing levers on the huge "interlocking machine" seen in the museum photograph, above. The interlocking machine, made by Union Switch & Signal Company, was state of the art for the time, and controlled the actual railroad yard switches by sending electric signals down to the yard, which signaled the compressed air-powered yard switches to move.

The interlocking machine is long-gone, but the train director's desk remains.

Original "candlestick" telephones were found to replace the originals. They are mounted on the table exactly as they had been in 1933. One of them has had modern mechanisms installed and is a working phone.

The track diagram board, which is still on display, worked in conjunction with the interlocking machine and mapped out the workings of the yard below. It's 5 feet tall, 42 feet long and originally contained more than 682 indicator lights.

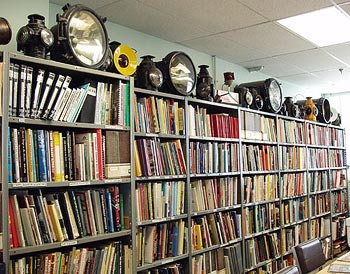

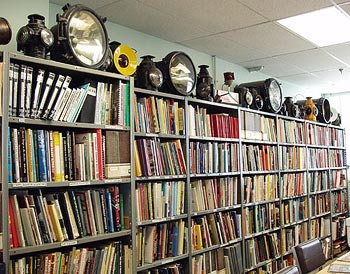

The signal maintainer's room was converted to a large railroad library.

At both ends of the main room, large illuminated clocks were restored. The general restoration effort of Tower A was a massive undertaking by the

Cincinnati Railroad Club, which had been a tenant of the station since 1938 - the longest and last tenant of the building. In 1989, the Museum Center and the Cincinnati Railroad Club agreed that the club should move into Tower A. Seventeen years of neglect had inflicted heavy damage on the tower and it had to be brought up to code, as well. Ultimately, the effort was successful although some of the finer work continues.

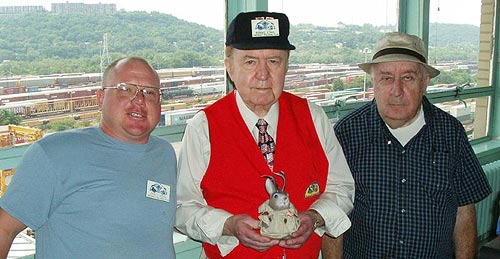

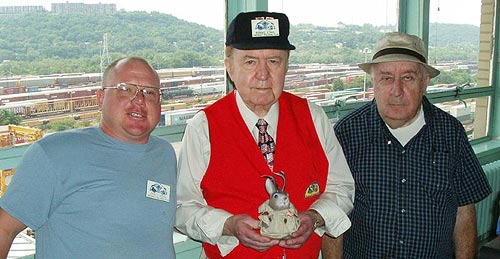

Cincinnati railroad Club members (L-R) John Vogel, Ronnie Stahl and Don Patrick gave us lots of background information on the tower. Stahl worked in the tower for many years and was quite informative to visitors.

The club operates a railroad museum in the main room of the tower.

While there is no model train layout present, there are a few examples, including this fine toy replica of a very early Union Pacific diesel; I'm pretty sure this was called the M-1000.

The main attraction to me is still the real trains, from an unusual vantage point.

Tower A is open to the public at no charge every Thursday 8PM - 11PM, every Saturday 10AM - 5PM, and the First and Third Sundays of each month 12PM - 4PM, according to their website at the time of this writing.

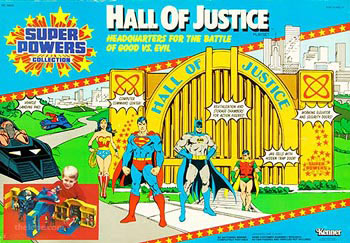

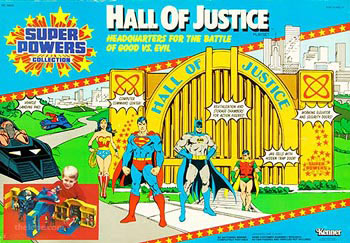

Oh yeah, the pop culture thing: If you think the station looks naggingly familiar, you may, like me, have the unfortunate memory of the Hanna Barbara cartoon series, "Superfriends." Yes, it was a travesty to true comic book aficionados and one

cheap bit of animation, but they did choose a good model for the Hall of Justice - that's right, the resemblance to Cincinnati's Union terminal is unmistakable.

You could even (kind of) have your own Cincinnati Union Terminal playset.

And there's more pop culture to come: The old Superfriends series had been parodied in South Park's episode,

Super Best Friends, in which Stan fights a cult leader with the help of Jesus, Muhammed, Buddha, Joseph Smith, Krishna and an Aquaman look-alike who are headquartered in the Superfriends' Hall of Justice. The animated version of the train station was also seen in the Family Guy episode,

A Hero Sits Next Door, in which Peter Griffin plays strip poker with the Justice League. I think it may also have shown up in Harvey Birdman, Attorney at Law episode,

A Very Personal Injury, in which Apache Chief, a member of the Superfriends, spills a cup of hot coffee in his lap and can no longer "grow large."

Yep, art deco, trains, natural history and a contribution to late night parody cartoons - what more could one ask of one building? We were there for five hours and didn't see nearly everything, but it kept four adults, two kids and one undercover jackalope quite interested.

New photo and information, added September 2008 - The Justice League

comic book now portrays a Justice League headquarters based on the Cincinnati Union Terminal. Somehow, that just seems right.